"Seeing Bowie perform ‘Starman’ on Top Of The Pops was like that moment in The Wizard Of Oz, of going from B&W to colour"

Queer music (and queer culture, generally) is having a renaissance right now but we also have a rich and diverse history, some of it obscure and hidden… until now. For the glorious Martin Aston has written the definitive social history of LGBTQ music, Breaking Down The Walls Of Heartache: How Music Came Out. Loverboy’s Fallon Gold caught up with him to swoon a bit and talk about the heroes we lost last year, surprising queer finds and whether Mariah is really bi…

While people have written about queer music and musicians before they never have as thoroughly – and may I say, as engagingly – as you have with BDTWOH. Why do you think there was this gap given the subject and the wealth of examples?

There’d been a handful of books in the Nineties – John Gill’s Queer Noises: Male and Female Homosexuality in Twentieth-century Music, Richard Smith’s Seduced and Abandoned: Essays on Gay Men and Popular Music and the late Kris Kirk’s A Boy Called Mary: Kris Kirk’s Greatest Hits, plus various academic studies. But they were all collections, of essays or reprised magazine features, split across genres – punk, disco, glam, etc – or various artists, and never as a chronological narrative – in other words, as a document of social and music history. Which always amazed me, though I was thrilled that no one had beaten me to it. Maybe it’s the fault of publishers, who don’t feel LGBT+ culture has a broad enough appeal, or think that the culture is associated with theatre, film and literature much more than music, because of a perception that ‘gay’ music (which seems to exist as a genre, as opposed to ‘queer’ music or LGBT+ music) is molded from dance music, Broadway musicals and divas – music rooted in theatricality, image and glamour, whether admitting a vulnerability or not, with a degree of artifice, and so, not to be taken seriously. It’s ridiculous, given it’s 2017, and LGBT+ performers are omnipresent, even in those formerly homophobic genres like hip hop and country. But that perception still exists in the mainstream media, and even sometimes LGBT+ media too. Certainly, all the aforementioned books concentrated on the usual suspects – Bowie, Sylvester, Pet Shop Boys, Frankie Goes To Hollywood, George Michael – and on men, which was mirrored in Channel 4’s hopeless Queer As Pop: From Gay Scene to Mainstream – just the same old rehashed stories (and dealt with in an hour, including ad breaks!). While all those performers were incredibly important, as pioneers who helped music ‘come out’, there are all these names and songs that history had forgotten, from the decades before Gay Lib, when it was illegal, or morally reprehensible, to state your sexuality and/or sing about it, and even by the 1960s, you didn’t have ‘celebrity’ interviews where people discussed their inner lives. I discovered so many compelling (and of course, often sad, or tragic) stories, and songs, about a host of artists I’d never heard of through the years; they often preceded the more famous names, and now I get to write about them, and bring them back to life. Given the misery of LGBT+ life in Russia and parts of Africa, it’s more important than ever to show how far we have come, from the closet to the charts, to borrow Jon Savage’s line.

You edited a series of books about women who are camp and queer icons: Judy, Babs, Aretha, Billie. Would you say that there is a separation or a connection between queer musicians and musicians who appeal to queers? I’m thinking here of the cliché of gay men loving divas (as a queer woman who loves divas I’d like to broaden this out to queers loving divas)

There does seem to be a disconnect between queer musicians and musicians who appeal to queers, historically anyway, though more among gay males than lesbians. Perhaps it’s down to history: for queer men to express something in music that spoke of their sexual difference, for a long time, they had to convey it in code and subtle suggestions via their image, which is how their queer audiences assimilated it. Again, it’s bound up in theatrical presentation, projection, artifice, etc., because people couldn’t be upfront and open. After Gay Liberation, gay men as a community did not demand, or consume, music that mirrored the complexity of their emotions; they preferred the sound of liberation, escapism, etc., which tied in to their social pattern of clubs/bars. Music of an introspective nature, that lamented the closet and homophobia, was not required at a time of celebration. And if they did want to admit to feelings, and vulnerabilities, they wanted to do it through the very strong female characters, who projected it BIG, in their music and personal lives, with a real theatrical and camp approach – in other words, the divas.

Maybe because lesbians didn’t have the same club culture, and a different perspective, they embraced that introspection, and (cliché alert) getting in touch with their feelings, which feminism and the consciousness-raising of the late 60s and early 70s had encouraged. Look at the success of 70s ’Women’s Music’ (as the introspective folk-based genre became known), artists such as Cris Williamson, who sold half a million records of her debut album on the lesbian-identified, lesbian-staffed, US record label Olivia, while similarly introspective gay male singer-songwriters such as Michael Cohen and Steven Grossman sold pitifully in comparison. I remember when clubs (Popstarz, Duckie) sprang up in London in the mid-90s, playing more indie-style pop, mixing it up with glam, punk, rock etc, it was revolutionary. Things have progressed and changed, with artists such as John Grant, who is unequivocally out (ranging from tragedy to… misery! But with lots of humour and camp) in his lyrics and interviews, and sold out the Royal Albert Hall last year – and a real mix of straight and gay couples. And the biggest cheer of the night was when Kylie walked on stage, in a silver gown! People still want their escapism.

We lost some profoundly key queer performers last year: Bowie, Prince, Pete Burns, George Michael. But the collective mourning of these greats has only highlighted their importance for our cultural landscape, don’t you think?

It’s astonishing how the majority of those shock losses in 2016 were queer performers. And though the nature of their passing, and their personalities, and the way they went about their lives, were different, perhaps there was a common theme of people who felt they had to play a part, that it was difficult to be who they felt they were. I think people respond to drama, emotional and physical, and we make gods out of our artists, especially in the realm of projection (film, theatre, musical performance). We love the fantasy, the costumes, the beauty, the ‘glamour’, the very performance, the way these performers can do it so well, and so evocatively, to live out our lives/thoughts/fears, as it were, to save us the hassle and the struggle. And we’re at our most impressionable when we’re young, late childhood or early teens, when artists such as Bowie, Prince and George would have impacted on us. Seeing Bowie perform ‘Starman’ on Top Of The Pops remains the deciding, dividing factor in my life – there was life before that performance, and life after… like that moment in The Wizard Of Oz, of going from B&W to colour. Their queerness – their otherness, as outsiders, despite their mainstream appeal and superstar status, and their ability able to mutate, and keep us enthralled, entertained and mystified – only amplifies these feelings. Also, the people we’re talking about here were all – ironically – survivors, with a kind of heroism to them, which made it doubly harder to lose them. Plus, they’re gods, so they’re not meant to die. Also, as we’ve grown up with them, we feel our own mortality.

Because of the amazing depth to the book you’ve unearthed some amazing obscure queer music folks. Who are some of your favourites?

There are numerous, right from the start, with British music star Fred Barnes, whose song ‘Black Sheep Of The Family’ was the earliest lyric (1907) I could find that, in hindsight, talked about being gay, in the code of being different. The fact he was caught in Hyde Park with a topless sailor only compounded it! It’s tragic that many pioneers – those first in their time, and/or their genre, to come out via coded lyrics or stage persona, or even bolder declaration – are long dead, and having existed in the era before celebrity interviews, their thoughts still escape us. But two US stars, Bruz Fletcher (peak period 1930s) and Frances Faye (peak 1950s to 1960s) particularly appealed, and are linked too. Fletcher was similar to Cole Porter in background (very rich) and song form (witty, suggestive, camp), though far more blatant in his homo-erotic words than Porter – and far less successful (he killed himself when his boyfriend left, work dried up, and alcoholism took over). Faye covered his song ‘Drunk With Love’ as part of her cabaret act, in lesbian and mixed cabaret clubs: no typical glamour-girl, she made up for it with brassiness and humour. She was very diva-sized. I’m very fond of the UK trio Handbag, who were the one bona fide gay glam band, with songs such as ‘Leather Boys’ and ‘Closet Queen’. But, apart from Tom ‘Glad To be Gay’ Robinson who mentioned them in a 1975 interview, and the gay press, no one knew about them. Their one album, Snatchin’, was only released in Italy. I talked to their singer and songwriter, Paul Southwell, at length, and the music really stands up. I love some of the earliest queer rappers like Age of Consent, Cyryus – the female Eminem! – Rainbow Flava, Deep Dickollective.

But the one story that rises above all others for me is the Roc-A-Jets: it’s hard to imagine there was an all-lesbian – let alone an all-female – rock’n’roll trio in the 1950s. Now that’s brave. Lesbians were exempt from the law in a way that gay men weren’t, on the risible basis that Queen Victoria didn’t accept that women had sexual feelings. And there was the belief that if they did make sex between women illegal it might bring the ‘act’ to the attention of more women and so encourage it! But Baltimore in the Fifties was still conservative and bigoted and if lesbians didn’t fall foul of any law prohibiting sodomy, they were regularly hassled by the police, regarding the number of ‘male’ items of clothing they wore; three or more, and they could be arrested. Also, two of the band were mothers (they’d married, and then divorced, before the band had formed) and there was always the fear they could have their kids taken into custody. But they played shows in a couple of lesbian bars and had quite a following, who would mimic the band’s outfits – white shirts, black trousers, bootlace ties, they looked like a little troupe of Buddy Hollys and Roy Orbisons! Some fans would leave the house in their everyday clothes and change somewhere along the way into their gig clobber. Straight couples would see them play too and there were fights with jealous boyfriends who didn’t like their girlfriends cheering on – and maybe more? – the band. I know all this because lead singer and rhythm guitarist Jo Kellum is still alive, in her eighties, and very lucid. Original drummer Edie Lippincott is too deaf to do interviews, but she sat in while I interviewed Jo on the phone. Sadly, singer-mother and gig commitments meant they never recorded anything, though a short clip of them playing live exists courtesy of a member of the audience. And the band survived into the 1960s. Sadly, Roc-A-Jets lead guitarist Jan Morrison died in 2007, so I couldn’t get her story, and there were times when I was limited by what I could write about artists because they were long gone, and so little was written about them at the time.

Who, for you, was the most surprising person for you who you weren’t aware was queer until you researched for the book?

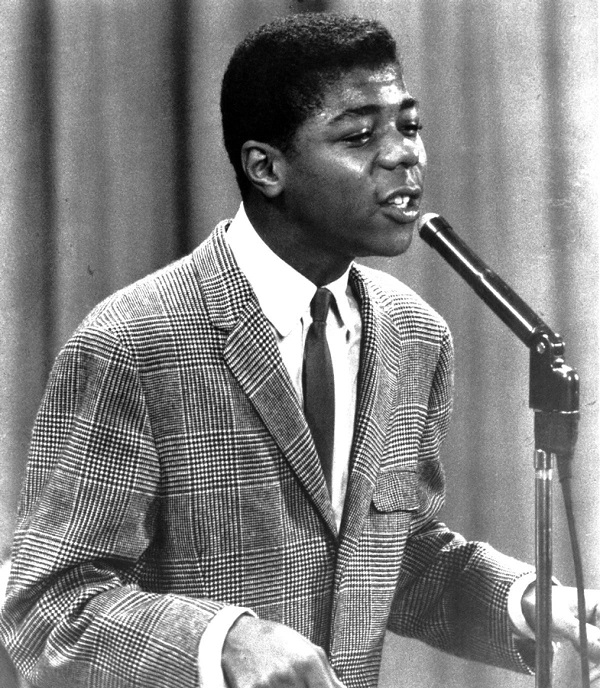

I can only think of one such revelation – teenage doo-wop sensation Frankie Lymon, but that’s because someone claimed to have had an affair with him, so I don’t know if he was gay, or just bi… but he was a teen phenomenon in the 1950s, and went off the rails spectacularly, but that might have been because he was black, or had major success far too young, than any issues over his sexuality: Otherwise, I either knew artists were queer, or I’d never heard of them.

Yeah, I was really surprised about Frankie too. Ronnie Spector writes about him turning up at her house, drunk and lascivious, when they were teenagers. I wonder if that was to cover up his gayness, or whether he was just… drunk and awful! Where do you see queer music going next?

It’s already gone everywhere, in every genre imaginable, except for reggae and raga. But amazingly, Sam Smith is the first openly gay performer to have a US number one album. Maybe this will become commonplace. Next up, the first pop-musical trans performers of music, in line with the increase in visibility of trans actors. We have successful trans rockers such as Laura Jane Grace of Against Me! But she transitioned after the band became well known, and it would be great to see a trans artist, from the get-go, taking over. Also some belated recognition of female-to-male trans artists.

What’s your favourite Mariah Carey song? (we believe the rumours about Mimi and Da Brat so, for us, MC is a queer performer)

I make a point in the introduction of my book that the story is about the LGBT+ performers of popular music, rather than artists who have an LGBT+ fanbase, such as Kylie Minogue or Mariah Carey. And until Mariah says something, or writes a lyric, about being bi, I’m not having it! And adopted gay anthems such as Abba’s ‘Dancing Queen’ don’t have any part in my idea of what this history is (though by comparison Rod Stewart’s ‘The Killing of Georgie’ single, from the same era, does. Stewart wasn’t gay, but his song was the first to describe a gay man, and sympathetically, and even feature the word ‘gay’, in a top three single). I didn’t make much of Whitney Houston’s bisexuality either because it didn’t further my story (while Madonna and Lady Gaga did because of their songs and personas). And because of my musical tastes – I grew up in glam and punk eras, I’m, much more ‘left-field’ and ‘indie’ (though I love electronica as much as folk) than anything – I don’t own a single Mariah track. So, if you’re going to press me, I’m going to have to say Whitney’s ‘Saving All My Love For You’! Just a fantastic, slinky song, and brilliantly sung.

Breaking Down The Walls Of Heartache: How Music Came Out, is published by Little, Brown