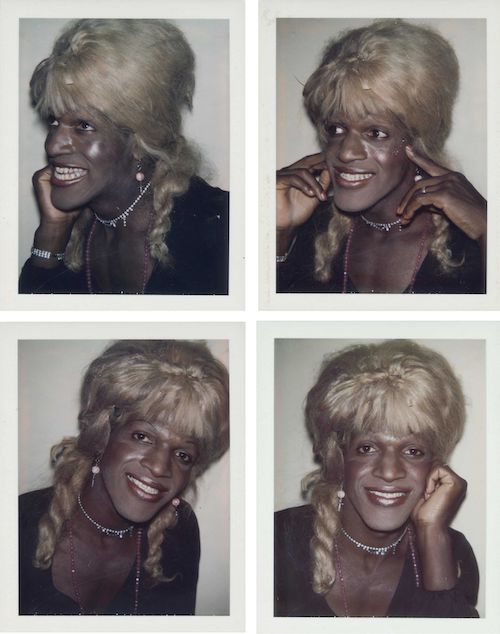

Yesterday we began our look at five Black LGBT heroes as part of Black History Month. Today we continue, with Mzz Kimberley writing about New York’s legendary drag queen and activist Marsha P. Johnson, who was a leading figure in the Stonewall Riots of 1969. Without this woman there may have never been a Pride. Plus, as an aside, The New York band Antony and the Johnsons fronted by trans singer Antony Hegarty are named after Johnson.

Marsha P. Johnson (1945 – 1992)

When I was a kid I met this character on the streets in New York, I thought she was mad. Coming from a small town she really shocked me as I never saw any one like her. Years later I discovered, that the woman I met was my absolute treasured icon. After being white-washed out of LGBT history, her story is now being shared more than ever. I was lucky to have been in two productions where I portrayed characters based on ‘Marsha P. Johnson’, one being ‘Closets’.

Johnson moved to Manhattan from New Jersey when she was 18 in 1966. She said she was ‘no one’ until she came to New York and became a drag queen. She supported herself mainly through sex work but also performed in experimental theatre company Hot Peaches and was photographed by Andy Warhol.

Johnson chose Marsha P. Johnson as her ‘drag queen name’ because everybody used to call her ‘Michelle’, and she claimed, ‘I was a little boy and I didn’t think that was a nice name for a boy.’ Walking down 42st, she got the name ‘Johnson’ from Howard Johnson’s restaurant. The ‘P’ in her name stood simply for ‘Pay it no mind’, as recalled by Bob Kohler, one of her fellow friends and activists in the gay movement, who was bailing her out of jail when the judge in Johnson’s case asked her what the ‘P’ stood for. Johnson snapped her finger and said ‘Pay it no mind.’ Humoured by the response, the judge agreed and let her go. Johnson would also use the saying sarcastically when questioned about her actual gender.

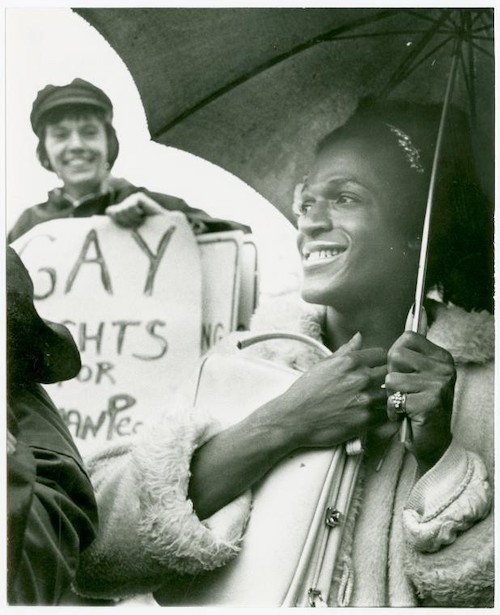

On the early morning hours of June 28, 1969, the Stonewall uprising occurred. Next year will be its 50th anniversary. Johnson was one of the first to fight back in the clashes with the police during the uprising. The riots reportedly started at around 1:20 that morning. According to David Carter, in the book, Stonewall: The Riots That Sparked The Revolution, it was stated Johnson, on the first night, ‘threw a shot glass at a mirror in the torched bar screaming, “I got my civil rights”‘, while on the second night, Johnson ‘climbed on top of a lamppost’ and dropped a heavy object into the windshield of a police car.

Following the Stonewall uprising, Johnson joined the Gay Liberation Front and participated in the first Christopher Street Liberation Pride rally on the first anniversary of the Stonewall rebellion in June 1970. One of Johnson’s most notable direct actions occurred when she and fellow GLF members staged a sit-in protest at Weinstein Hall at New York University in August 1970 where administrators had cancelled a dance when they found that it was sponsored by gay organizations. Shortly after that, she and close friend Sylvia Rivera co-founded the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR) organization (initially titled Street Transvestites Actual Revolutionaries), and the two of them were a visible presence at gay liberation marches and other radical political actions. In 1973, Johnson and Rivera were banned from participating in the gay pride parade by the gay and lesbian committee who were administering the event stating they ‘weren’t gonna allow drag queens’ at their marches claiming they were ‘giving them a bad name.’ Their response was to march defiantly ahead of the parade. During one LGBT rally in the early ’70s, a reporter asked her why she was there, Johnson shouted to the microphone, ‘Darling, I want my gay rights now!’

Johnson died shortly after New York Pride in 1992. Her body was found floating in the Hudson River. Initially police ruled her death as suicide. Several people came forward to say they had seen Johnson harassed by a group of ‘thugs’ who had also robbed people. According to Wicker, a witness saw someone engaging in a fight with Johnson days prior to her death calling her a homophobic slur in the process and later bragged to someone that he ‘had killed a drag queen named Marsha’ at a bar. Despite a campaign from Johnson’s friends and vigils at the site where Johnson’s body had been found, initial attempts to get the police to investigate the cause of death were unsuccessful. In November 2012, activist Mariah Lopez finally succeeded in getting the New York police department to reopen the case as a possible homicide.

Johnson was cremated, and her ashes spread over the same river where her body was found as a special memorial by her friends.

The documentary, The Life and Death of Marsha P. Johnson, is available on Netflix now. Alternatively you can watch Laverne Cox, Candis Cayne, Janet Mock & others discuss Marsha below.